What Should The Climate Corps Actually Do? Part 1

Let's use the most productive agricultural system in history to reclaim abandoned waterways

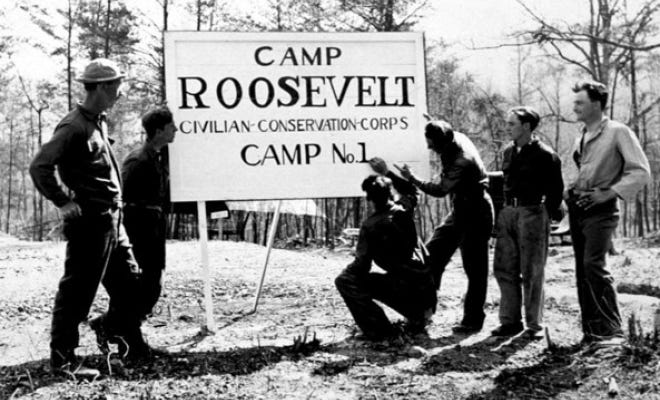

One of the greatest government programs in history was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). This New Deal initiative directly employed nearly 3 million people (about 2.5% of the country’s population, equivalent to 8.3 million people today) in conservation work.

Lasting from 1933-1942, the CCC’s list of accomplishments is staggering. It built 30,000 miles of terraces, planted 3.5 billion trees, constructed 3,000 fire lookouts, created 711 state parks, and built the country’s first downhill ski slopes.

But not all of the CCC’s work looks so great in retrospect. It built plenty of bad infrastructure in good places—mostly on behalf of the military—and it did a lot of logging and wetland draining; it wasn’t guided by an ecological ethos, to say the least. Nonetheless, it offers us a framework for what a mass employment initiative could look like to tackle the myriad ecological crises of the present.

So, if we were to use that framework to create an ecologically-minded Climate Corps, what kind of work would it do? It could certainly do the obvious stuff: reforestation, invasive species removal, various climate resiliency projects, and so on.

But in the innovative spirit of the CCC, I want to highlight some ideas for ecological infrastructure that could transform this country’s capacity to feed itself, sequester carbon, and support biodiversity, all in a way that would last for generations.

For Part 1 of this series, we're going to look at what may be the most productive and self-sustaining agricultural system in human history. This is a method for growing food that we could use to turn abandoned waterways into the most productive sites for agroecology in the country.

Chinampas

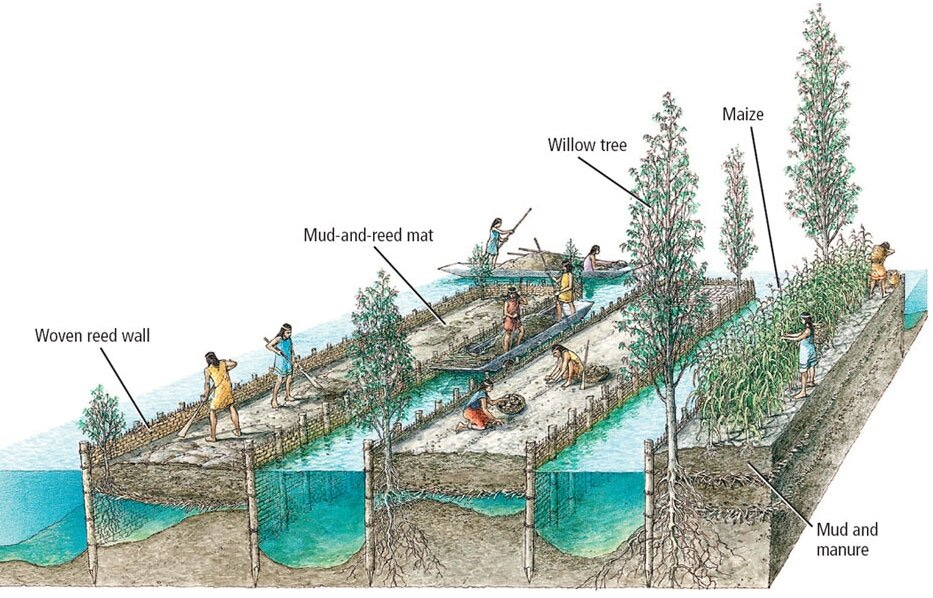

Chinampas are artificial floating islands or peninsulas built into shallow waterways. This ancient Mesoamerican agricultural technique still exists today, most notably in Xochimilco, a major tourist attraction in what is now a suburb of Mexico City. Chinampas have been studied extensively, both by archaeologists and contemporary agronomists, ecologists, and others, who have demonstrated that they offer exceptionally high-yields from low-inputs, while providing critical habitat to sensitive wildlife (most notably the adorable Axolotl, which is uniquely adapted to chinampas.)

Chinampas are ingenious structures. They're built by sinking log posts into the bottom of a shallow body of freshwater, then weaving a fence-like structure between them. These rectangular containers are then filled with organic matter, usually a combination of muck and brush. This is piled high enough to keep the top of the bed permanently above the high water mark. The edges are then planted with willow to prevent them from eroding.

The top layer of the bed is planted with crops. As the plants make use of the water and it evaporates from the surface, capillary action and roots draws it up from below, meaning that established plants in chinampas never need to be irrigated. Additionally, since the soil isn't being irrigated from above, nutrients aren't washed down and out of the system; this not only keeps them in place for the benefit of the plants, it contributes to uncommonly clean water in the surrounding channels. As a consequence, they support abundant wildlife while making it easy and safe to raise fish and waterfowl between the plots.

The channels between the beds can be very productive as well. In addition to being used to raise fish and waterfowl, they can be covered in arching trellises or used to grow aquatic plants. The trellises can support vining crops which can be harvested via canoe, or they can be planted with crops that drop their fruit into the water, a passive method of feeding the fish and waterfowl. Aquatic plants can serve the same functions; things like lotus, wapato, wild rice, and pickerel weed are a natural fit for chinampas in North America.

A huge benefit for growers is that the thermal mass of the surrounding water moderates temperature fluctuations, extending the growing season by reducing the incidence of frost while providing a lower-stress environment for plants, which in turn improves yields significantly. Reducing the effects of wild temperature swings is especially important as we enter an increasingly volatile stage of climate change.

The soil in chinampas is renewed by periodically dredging the sediment from the bottom of the channels, which accumulates when leaf litter and waterfowl/fish manure sinks to the bottom. This supplies an endless source of high-quality nutrients to the system, and prevents anything from going to waste. It's a closed-loop system.

Chinampas are also huge carbon sinks. The logs and weavings used to construct the beds are almost entirely submerged in water, which means they never decompose. The beds themselves and all of the vegetation piled into them are of course carbon-based, too. (Great potential for synergy exists with invasive species removal in the areas surrounding chinampas, since all of that herbaceous and woody material could be piled into the beds, like a floating hugel.) And the willows supporting the edges of the beds mature into a low-density forest. By constructing an extensive chinampas system, we could sequester astronomical amounts of carbon while simultaneously improving habitat.

So where could an American Climate Corps build chinampas? I propose starting with America's 3,000+ miles of abandoned canals, mostly built during the 19th Century. Some of these canals have been integrated into lightly used public parks, but many are entirely neglected. Converting them into chinampas would turn derelict infrastructure into a hugely productive, attractive, and valuable resource.

Doing so at scale would be a huge undertaking but exactly the right kind of project for the Climate Corps. As industrial agriculture declines—either due to a deliberate shift away from it or as a result of climate pressure—new sources of food that are resilient and fossil fuel-free will be needed. Chinampas demand a lot of labor upfront, but once they're built, they're astoundingly low maintenance and long-lasting. That is the kind of infrastructure we should be building.

And how lovely would it be for new communities centered around small-scale farming to spring up alongside the old canals? One can imagine floating down the renovated canals—hundreds of miles long—lined with lush little farms jutting out into the water, stopping for meals at farm cafes and staying at B&Bs in town. A linear feast!

For daily updates, you can follow me on Twitter, Instagram, Bluesky, and Mastodon.

> One can imagine floating down the renovated canals—hundreds of miles long—lined with lush little farms jutting out into the water, stopping for meals at farm cafes and staying at B&Bs in town.

Loved this. It is delightfully evocative of News From Nowhere.

The Climate Corps is a brilliant (even solarpunk idea) and building chinampas in the U.S. is too. Thanks for sharing :)