What Is The Purpose Of Homesteading?

On the past & present of an increasingly popular lifestyle choice

"Homestead" is an ancient word. It comes from the Old English (5th-7th Century) compound word hamstede, meaning "home" and "place." "Home" did not refer to a detached rural house but a village or town, and "place" referred to a fixed location, in contrast to a seasonal nomadic stopover. It was a permanent communal settlement, a far cry from what we think of today when we hear the word "homestead."

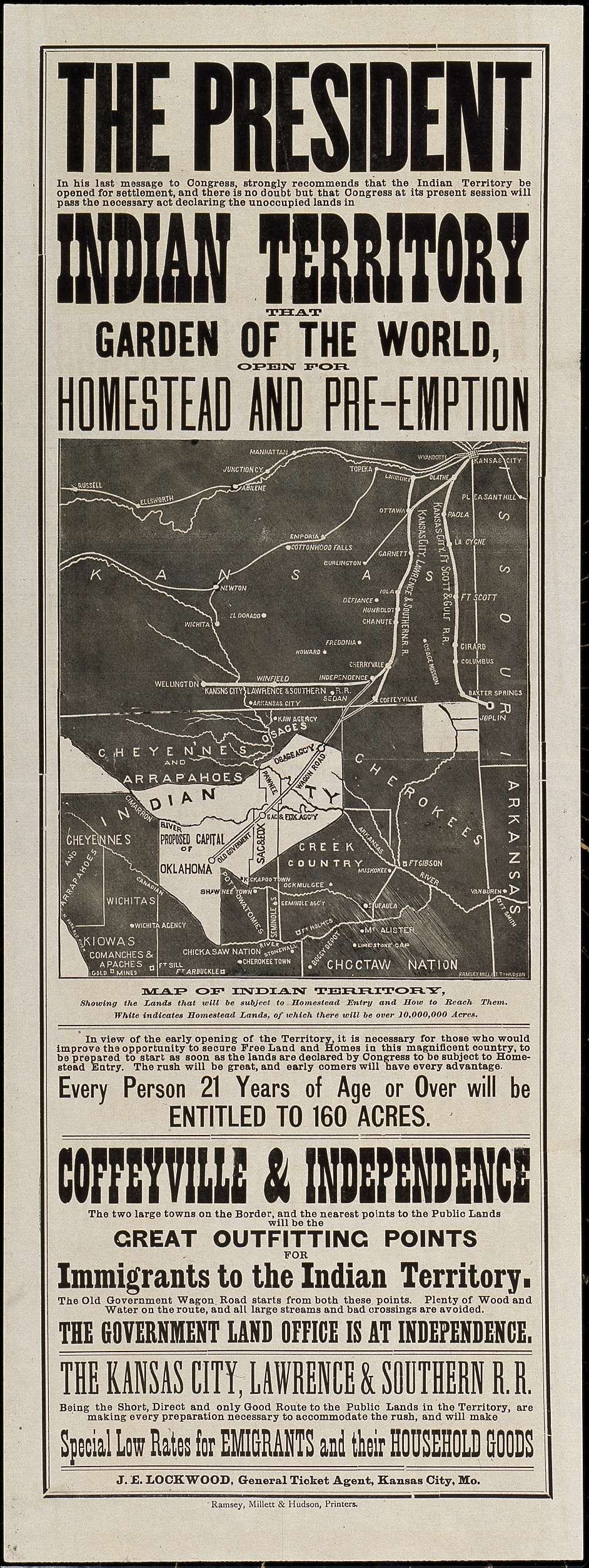

But language changes over time, and the contemporary meaning comes from the Homestead Act of 1862, a federal law granting 160 acres of public land to virtually anyone willing to work the land and build a residence on it within 5 years. In typical American fashion, the Act represents both this country's most democratic impulses and its worst, ugliest history, all in one.

Mass land distribution was one of the central demands of 19th Century agrarian populists, who organized a coalition with labor unions and progressives to eventually pass a homestead act in 1860. But it was opposed by the Southern slaveocracy, who wanted to ensure that western territories became slave states, along with Northern capitalists, who feared a labor exodus. Boeing to the combined pressure, the act was vetoed by the slavery accommodationist President James Buchanan.

Abraham Lincoln ran on passing a new homestead act, and he was able to follow through on his promise after winning the election of 1860. Southern lawmakers quit Congress en masse to form the Confederacy, clearing the way for its passage two years after the election.

The Homestead Act of 1862 was radically democratic, especially for its time. The only requirements were a small filing fee, a commitment to work the land for 5 years, and that the recipient be either 21 years old or the head of a household. Thus, in the midst of the Civil War, landless people of all types—freed slaves, single women, urban factory workers, everyone—could acquire land with only a promise of labor. Non-citizen immigrants even became eligible; the only people (initially) excluded were ex-Confederate soldiers. 10% of the entire U.S. landmass was doled out under the Act. It’s no exaggeration to say that it changed the course of history.

The picture gets decidedly more dreary, though, when you consider why that land was available to distribute in the first place. The conquest of North America was one of history's most gruesome acts of genocide, and whatever egalitarianism motivated the Homestead Act rested on a foundation of mind-numbing horror. The land distributed under the Homestead Act—which remained in partial effect until 1988—was fertilized with the blood of millions, many of whom were still alive at the time of its passage. It both relied upon the genocide of the past and dramatically facilitated its continuation.

The people who had resided on North American lands for millennia were largely exterminated, the few survivors forced onto hellish reservations. One irony of history is that Native peoples were very briefly excluded from the Homestead Act on the grounds that they were not legally recognized as people, but this rule was changed in the interest of assimilation to allow them to participate if they renounced their tribal citizenship. Those who participated were eventually forced off of or defrauded of their homesteads, anyway.

The history described above is as relevant as ever. Land distribution did not prove to be a cure-all for the ills of industrial capitalism, as agrarian populists, labor unions, and progressives had hoped. It temporarily opened a pressure-release valve on the broiling cauldron of capitalist industrialization, allowing for a new class compromise to emerge. Industrial wages in the North rose as surplus labor moved West; many freed slaves found an exit from the feudal society of the American South; and westward expansion created a new class of railroad barons, who extracted much of the wealth generated by migrants. Homestead settlers became active participants in the continued ethnic cleansing of North America, and the conflicts they created served as convenient excuses for the state to accelerate its war of extermination against Native peoples.

The American countryside, meanwhile, was thoroughly conquered by capitalism. Rather than democratizing the means of subsistence, land distribution under the Homestead Act created a class of rural peasants toiling miserably to produce agricultural commodities. While the land itself was indeed a form of downward economic distribution, the end result illustrates the limits of such a program under capitalism.

Which brings us to today. Homesteading is now something that one buys one's way into. It once again seeks to democratize the means of subsistence by empowering individuals to supply for themselves what they would otherwise acquire from the commodity market, via growing plants and raising animals, processing the harvest, and generally trying to be as materially self-sufficient as possible.

It is, in short, a lifestyle choice. The purpose of any lifestyle choice is to lead a fulfilling, enjoyable life, and that is very much worth doing for its own sake. But it is a personal choice whose impact cannot extend beyond the individuals involved: homesteading—like any lifestyle choice—cannot make structural change, as its history amply demonstrates.

I am a homesteader, and it is the greatest source of joy in my life. I love every single day of it, and I deeply regret not doing it sooner. But the conclusion I draw from it is not that everybody should be a homesteader, but that everybody should be able to lead a thriving life.

To afford that opportunity to everyone requires transformational political and economic change. Not just a redistribution of wealth, but the radical democratization of our economic and political institutions and the dismantling of oppressive hierarchies. Only with those seismic changes can we create a world in which all of us can experience the daily joy and profound meaning that is our common right as people.

For daily updates, you can follow me on Twitter, Instagram, Bluesky, and Mastodon.

Interesting history, thanks for this! Makes me wonder what America would be like today if the migrants had assimilated into the indigenous culture and relationship with land rather than the horrific opposite of that...