This is the first in a series of newsletters elaborating on each point in the "Infrastructure Agenda for Municipal Eco-Socialism" I posted over on Twitter, a dying website owned by a megalomaniacal idiot. I'll be activating the chat function here on Substack and posting regularly on Notes once that is live in order to stay in communication with you all.

Okay, now on to municipal food forests!

What is a municipal food forest? It is tree-based perennial agriculture that serves the public good. Broadly, it is my proposal to put publicly-owned land to work via permaculture for the benefit of all, shifting us towards a world in which the means of subsistence are freely available and held in common. It replaces commodification with communalization, while preserving, regenerating, and improving our ecosystem.

But before I get into the details, let me say a couple of things about this agenda in general. This is not intended to be a one-size-fits-all program. Local variations such as climate, available land, and community-specific needs will dictate exactly how a municipal eco-socialist agenda is best implemented.

Okay, there's A TON more that I could say about all of that, and I will in the future. Let's get into municipal food forests!

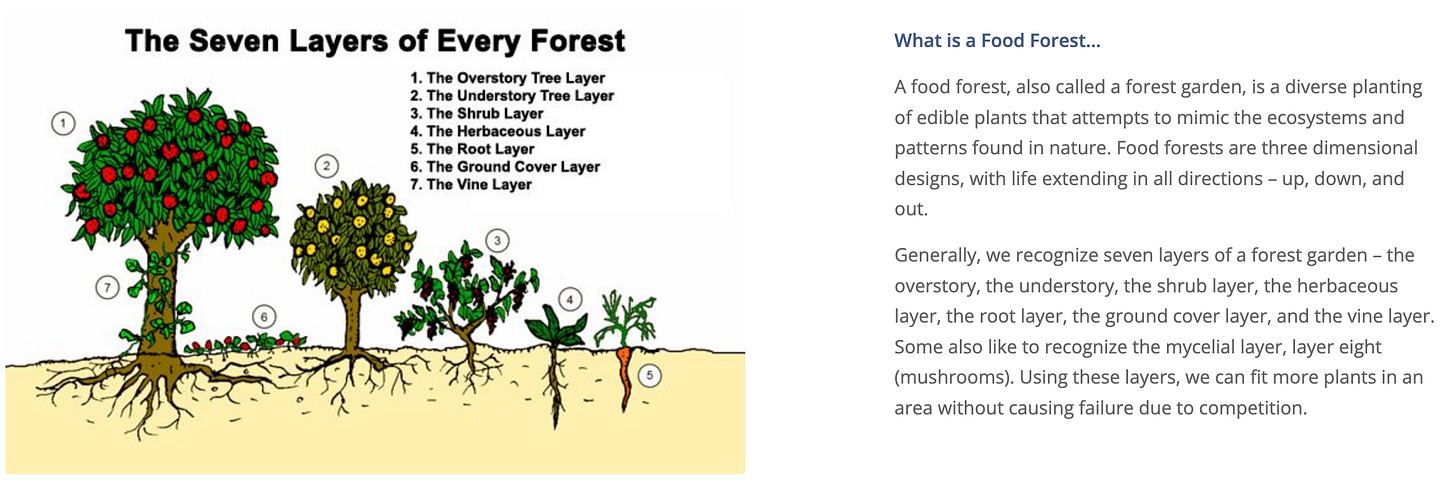

What is a food forest? Here's a nice visual explanation.

The goal of a food forest is to be a closed loop system: it seeks to generate its own inputs to the greatest extent possible. In the ideal scenario, the only labor input would be harvesting. If that seems far-fetched, consider that such plantings have survived for over 150 years without any maintenance, evolving to become vital foraging grounds for the descendants of the people who planted them.

This is the opposite of industrial agriculture, which is entirely dependent on off-farm inputs, with the absurd result being that each calorie produced requires seven to ten calories of input, primarily from fossil fuels. From an efficiency standpoint, industrial agriculture is a colossal failure.

Food forests, on the other hand, seek to reward laziness through good design. The result is that they require a decent amount of upfront work--as much in planning as in planting--but a well-designed food forest will require less and less input over time. It is wildly efficient in terms of calories, producing about, 2,100,000 calories per acre per year, even under suboptimal conditions, enough to feed two adults. I believe the actual number is about double that, but you can read the note at the bottom of this post to understand why.

Now let's do some quick back-of-the-napkin math to figure out the potential space for municipal food forests. A survey of 83 American cities found that they had an average of 12,367 acres of vacant land each, or 15.4% of their total land area.

If all of that were suitable for food forest planting, that would represent a theoretical food supply for 24,734 people per city. That, of course, is not possible because not all vacant land would be suitable, nor would it be desirable, since municipalities have other unmet needs, like housing. There is also the issue of ownership, which we'll get to in a moment.

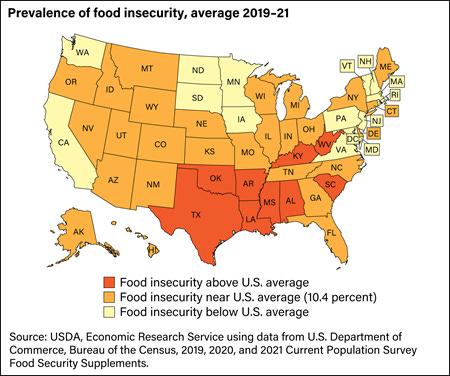

If we go one layer deeper on the data, the raw potential for feeding people actually looks even better. The reason is that the municipalities with the most vacant land and the greatest food insecurity are one and the same. In the South, cities average 20,011 acres of vacant land—and what would you know—that's where food insecurity is the worst.

So the potential for mid-sized cities to plant extensive food forests seems quite strong, although certainly we would not be able to meet everyone's food needs this way, nor would we want to. Cities should be dense; urban agriculture is an adaptation strategy for capitalism's failure to coherently manage land use. Ideally, we would have very dense, car-free cities with relatively small land footprints surrounded by agricultural greenbelts.

The potential for that type of arrangement in the near-term is greater in small, older cities and towns, which tend to get rural quickly after you depart Main Street. That is where municipal food forests could come much closer to meeting everyone's food needs without major renovations to urban infrastructure, owing to the land use patterns and smaller populations. Such municipalities are losing population in most places, but I am willing to bet that a small city that pursued an ambitious policy of municipal food forests would quickly reverse that trend.

Now: ownership. This is where we get to the "socialism" part of "eco-socialism." What distinguishes this agenda from a liberal/non-profit approach, is that it seeks to rebuild "the commons," a collective form of ownership that has been the norm in human history. In the grand scheme of things, it is only quite recently that land was violently stolen from the commons and commodified.

The process of reversing and evolving a historical trend that forms the foundation of our entire economic and political system will not be quick or easy. That said, as history shows, there are ways to approach it that minimize reactionary backlash. That approach is to make it a public good enjoyed by all. More than anything, what people really care about is quality of life, and improvements to it basically override everything else.

With that in mind, municipal food forests should start on land that is already publicly-owned. This would provide proof of concept and offer immediate improvement to quality of life. 40% of all the land in the United States is publicly-owned, with 8% of that owned by states and 0.5% by cities and counties. That is more than enough to get this program off the ground.

The best way to do so, in my opinion, is to start small but visible. Convincing a town council to permit a small food forest in front of the library is a pretty easy pitch, all things considered. If it goes well, more ambitious expansions become much easier. That expansion should focus on vacant land just outside of the urban core, allowing for future development to densify that core while producing agricultural goods a close as possible to the population.

So, let's say we actually managed to get a municipal food forest planted. How would it be managed? There are no shortage of options here, but on Twitter, I proposed putting it under the jurisdiction of the school system. This would allow for professional oversight by the grounds crew--who already have much of the infrastructure necessary for the task--along with input from students, who could be tasked with 'adopting' sections of the forest as part of their education.

Despite what some shrill freaks said in response to this idea, it is not serfdom for children but similar to the gardening that already takes place at many schools. Heavy lifting and large-scale management would be carried out by well-compensated, unionized professionals, while students would get the benefit of learning the light skills necessary for the food forest's maintenance, along with age-appropriate, hands-on lessons in biology, ecology, chemistry, and botany. Research has confirmed the myriad benefits to outdoor learning for schoolchildren of all ages, and one can only imagine the joy it would bring kids to nurture their section of forest throughout their childhood and adolescence.

However, there are plenty of other options. A municipal food forest could be managed by a town's grounds crew or highway department, who again already have most of the pieces in place, or by volunteers/service organizations.

And what of the food itself? I suggested a food UBI in my original post, which appeals to me because it directly contributes to decommodifying the means of subsistence. Another option would be to send the food to public schools for their cafeterias, improving the quality and sustainability of what students eat. And yet another option is use some of the food in a town canteen, another municipal eco-socialism agenda item that I will expand upon in the future.

So those are the nuts and bolts. Looking at the details, this may not seem like a particularly radical agenda item, but it contains the seed for a much different world. The way to ensure that that seed propagates is via political organizing. For municipal food forests to contribute meaningfully to a shift away from capitalism, they would need to be part of a broader eco-socialist movement with a far-reaching utopian horizon.

I believe municipal food forests are a worthy political goal because guaranteeing the means of survival would dramatically alter the balance of power in our economic system while improving quality of life for all. Changing the balance in this way is essential because it prevents the greatest problem with system change: the temporary decrease in living standards while the new system gets up and running (the "transition trough problem.") This agenda improves quality of life now, while creating a floor for a system transition, making a successful move away from capitalism towards eco-socialism far more likely to succeed. It also smooths the way for other necessary reforms: if your food is free, dramatic increases in the cost of fossil fuels, for instance, will not be as concerning.

This sort of thing should be front and center for the Left's agenda at a time when inflation is the most pressing political challenge of the day. Programs like municipal food forests can resolve the false tension between lowering inflation and pursuing the aggressive ecological agenda we so desperately need. The municipal approach also resolves the biggest problem with existing urban food forests, which is burn-out. Volunteer run programs of this sort simply do not have the potential to making lasting, system-wide change. Incorporating them into a reinvigorated, radically democratic state will be necessary to build a new world.

For more information on permaculture and urban food forests, here are some articles worth reading:

The Rise of Urban Food Forests

Urban Food Forests: Demonstrating City Permaculture

Food Forest Movement Finds Fertile Ground in the Midwest

—The Last Farm

FOOTNOTE: There are a couple of major caveats to the study that is the source of the 2,100,000 calories per acre figure. The first is that the food forest studied is in a place called Coldstream, Scotland, which is about as hospitable an agricultural environment as you'd imagine based on the name. The second is that the food forest in question was planted 25 years ago with a mix of plants that was not designed for a well-rounded diet. Food forests have come a long way since then, and newly planted food forest with subsistence in mind produce calories much more efficiently.

i built one in my town, the town dumps snow on it every year, but it still grows...

Great post.

Another approach is guerilla gardening, just start clearing and planting common lands. We have undeclared/city owned land next to our place that was covered in invasives like Japanese knotweed and blackberry. I've been clearing it out and planting a food forest. Have been getting free and inexpensive plants from my previous gardens, Nextdoor app, and from an already established food forest.

Nature is exponential in that if you start a food forest, you will have an abundance of plants and clippings for other food forests.

Just do it, no need to wait for goberment approval for degraded areas.